Today, the European Commission has leaked its proposal for a “Data Act”, a piece of legislation that is supposed to include a revision of the Database Directive and the sui generis right for the creators of databases (SGR) it establishes.

What’s changing? Not much!

It won’t take a long read to understand what the Commission is planning to do with the sui generis right: not much! While fluffy language is included that explains how European courts have been working for over two decades to “sharpen” the definitions and our understanding of when this right applies and what it covers, the actual proposed change is a baby step. The European Commission merely suggests excluding machine generated data from the application of the SGR.

This is the core issue with the EU here. The European Commission is afraid to call a spade a spade. It must be apparent to the people working on this that the SGR is an obstacle to data sharing and innovation. Further, there is no known proof that this right has brought any added investment to database creation in the EU since its creation. Knowing this, the Commission takes the right step to limit its application so it doesn’t stop Europe in the field of machine generated data. But why do we stop here?

A little history

The Database Directive came into force in 1998 and the SGR is implemented in all EU Member States. Outside the EU, similar protection exists in the United Kingdom and the Russian Federation. In all other countries, such as the USA and Australia, there is no separate database maker’s right and databases can be protected if they fall under copyright law.

In 2015, the European Commission carried out a first evaluation of the Directive in which it stated:

“Is “sui generis” protection therefore necessary for a thriving database industry? The empirical evidence, at this stage, casts doubts on this necessity”.

European commission

In 2021, the European Commission launched a public consultation on the Data Act with a section on the sui generis right. The responses show that stakeholders largely don’t understand and don’t apply it.

A cascade of legal disputes over what this right does and where it applies has wasted stakeholders and investors years in front of European courts and we are still far from having a clear understanding of where and for how long this right applies. It could be eternal, it could cover entries. This scares people and organisations away from using otherwise available databases.

Why do we particularly care?

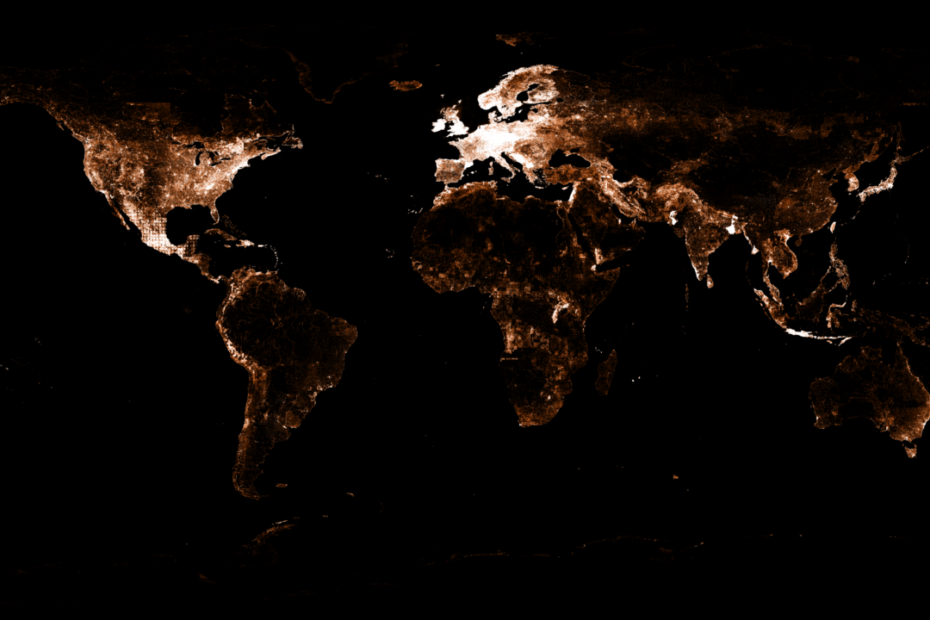

Wikimedia works on several projects that offer free knowledge to anyone, anywhere. One such project is Wikidata, a free knowledge base with currently 96,795,835 data items that anyone can edit and humans and machines can read. Wikidata is used by Wikipedia, by scientists, journalists, by larger companies such as Lufthansa and Air France, by smaller competitors like DuckDuckGo (to offer info boxes) and by start-ups. But Wikidata can only include data that is free. Our main issue with the sui generis right is that in many cases we don’t know whether a database is or isn’t protected by it, so we pass on it.

a simple solution is at hand

There is, of course, a very simple solution here. A solution that was recently applied to the Text and Data Mining exception in the Copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive. Databases (Article 4) should only be protected under the SGR if their creator has expressly stated so, for example through machine-readable means in the case of content made publicly available online. This would allow anyone who wants to apply the SGR to their databases, but it wouldn’t stop re-use of data in all the other cases.