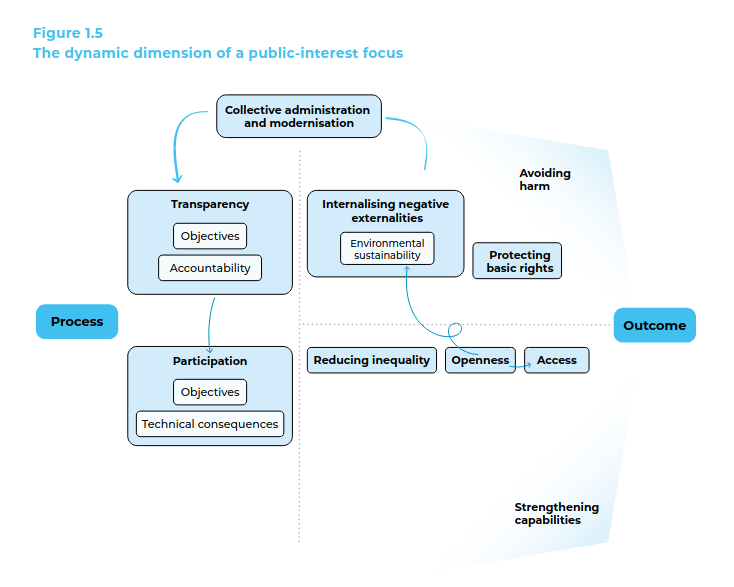

What do the European AI Act, the European Commission’s Data Strategy, the proposed US Digital Platform Commission Act and the German Digital Strategy have in common? They all name the public interest as a key objective. For good reasons, it is increasingly en vogue for digital policy to be designed as to foster the common good and serve the public interest. But what should public-interest digital policy look like? Wikimedia Deutschland has developed eight requirements against which digital policy projects must be measured if they are to serve the public interest. Transparency and effective participation are needed. Fundamental rights must be protected and damage to the community must be prevented. Digital policy should mitigate inequality, its outcomes must be open and accessible, and it must be collaboratively managed and renewed.

In this blog post, we summarize what these requirements mean for digital policy. The complete policy paper on public-interest digital policy you can read and download here.

The process of public-interest digital policy needs participation

For digital policy to serve the public interest, it is important that affected groups can get involved. Policy-makers need to involve also those social groups that may experience risks or negative technological consequences. Such expertise is often found in non-profit organisations and civil society associations, which often have less informal relations with government departments and politicians than companies and business associations. For participation to work, policy-makers need to provide transparency and create opportunities for participation that are adapted to the groups – and this is admittedly costly. The two requirements related to effective participation are:

1. Transparency: The planned process and objectives of a project need to be disclosed. There needs to be a clear plan as to who is accountable for the project and which perspectives will be incorporated, and how. This transparency is a prerequisite for participation.

2. Participation: Various relevant perspectives need to be incorporated to define the objectives of a digital-policy project and assess its technical consequences. Opportunities and risks need to be weighed up clearly and transparently.

Public-interest digital policy should create no public harm, but more capabilities

It should go without saying that digital policy projects should avoid creating harm. But time and again, ideas such as weakening encryption to enable surveillance of private communication put basic rights at risk. In addition, regulatory efforts are slow to address the high social costs of platforms, such as the psychological strain on content moderators or the environmental impact of resources used in short-lived devices.However, public-interest digital policy should, above all, strengthen people’s capabilities. Openness can make a major contribution to this, for example, if free and open software can be reused by everyone, or if open, interoperable platforms enable users to find the provider that suits them and to switch easily. Digital policy-makers should ensure that as many different groups as possible have access to the results and that those who are currently disadvantaged also benefit from digital services. The five requirements related to digital-policy outcomes are:

3. No negative externalities: Harmful impacts on the general public must be prevented; this is particularly true in terms of environmental sustainability.

4. Basic rights: Basic rights must be taken into account and protected – such as freedom of opinion, assurance of privacy, the integrity of IT systems and the basic right to social participation. Whenever balancing is required, it needs to be transparent and involve the groups affected.

5. Less inequality: The digital-policy project must reduce inequalities and help ensure ample capabilities for all. This requires, for example, internet access and media literacy, but also platforms that do not unilaterally impose conditions on their users.

6. Openness: The outcomes, products or findings resulting from the project need to be freely available. For example, software needs to be freely reusable and services need to be technically compatible with other services.

7. Access: The project must facilitate access to infrastructure, digital services, data or similar.

Collective renewal ensures public interest in the long term

Notions of public interest are changeable as are the perspectives of relevant groups. That is why there needs to be mechanisms ensuring a digital-policy project is updated in a way to continually serve the public interest.

A particular challenge is the tension between a market dynamic and a dynamic suited to the public interest. Does a digital-policy project need to compete with profit-oriented projects? If so, longer-term government funding may be needed to prevent commercialisation, which usually comes at the expense of openness and broad access. The organizational form, financial support and competitive environment must be designed to keep the focus on public interest for the long term. The last requirement related to renewal is:

8. Collective administration and renewal: Policy-makers must make the impacts and outcomes of digital-policy projects transparent. Continuous participation processes should be used to adjust the projects where necessary in order to promote public interest over the long term.

Applying the requirements to digital-policy projects

We applied the requirements to three digital-policy projects of the current German government to understand which requirements they implemented well and where they have shortcomings:

- the Sovereign Tech Fund, a funding programme for open source infrastructure;

- the Mobility Data Space, a platform for data exchange in the mobility sector; and

- the Data Institute, a digital lighthouse project to foster the sharing of data for the public interest.

In these examples, we found that participation is particularly difficult for most projects and even where government departments set up formal consultation processes, it is very unclear if they have any effect. Without participation, the outcomes often benefit unnecessarily narrow groups. Policy-makers hesitate to give the public interest priority over purely economic outcomes, often designing projects less open, transparent and accessible than they could be.

We also found that there are numerous ways in which digital policy can better serve the public interest, some of which set the overall direction of a project, but many of which represent small tweaks that may have simply been overlooked. Designing digital policy to serve the public interest is not a self-contained task, but a learning process in which policy-makers can and must open themselves to new thinking. The potential could hardly be greater.