In late 2021, the UNESCO General Assembly approved a new Recommendation on Open Science. All the member states agreed on a final version, that for the first time provides an official definition of what open science is, and that calls for legal and policy changes in favor of open science. As a recommendation is the strongest policy tool of UNESCO, “intended to influence the development of national laws and practices”, this is important news for the entire scientific community.

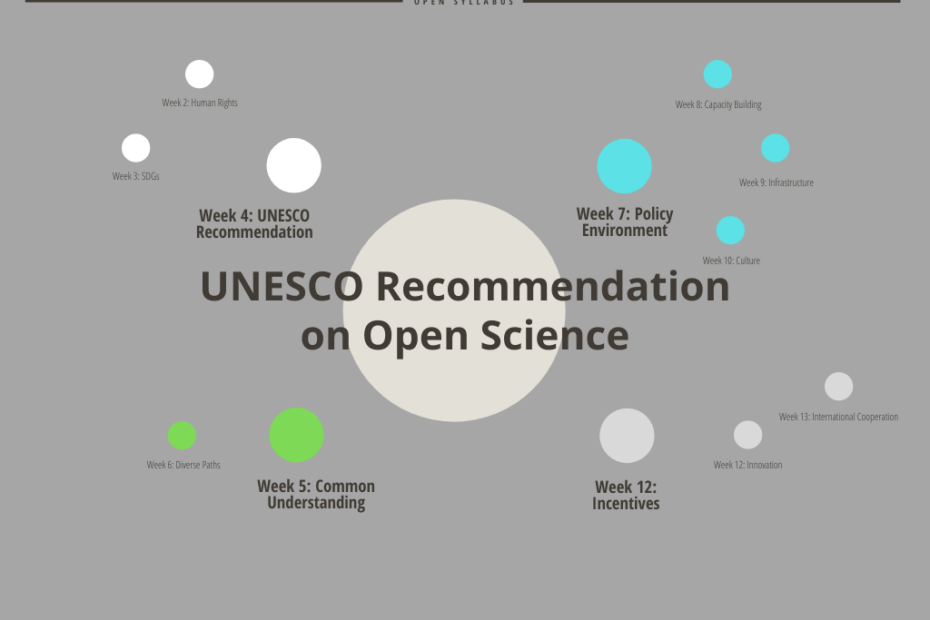

The recommendation presents a framework on, and principles for, open science. It aims to build a common understanding on the topic, and calls for publicly funded research to be aligned with the principles: transparency, scrutiny, critique and reproducibility; equality of opportunities; responsibility, respect and accountability; collaboration, participation and inclusion; flexibility, and sustainability.

It asks for more dialogue between the public and the private sector, and for new, innovative means and methods to be developed for open science. Finally, the recommendation stresses the importance of citizen science and crowdsourcing, and the need for cooperation between different kinds of actors, nationally and internationally.

In Sweden, the recommendation is currently being discussed with stakeholders. A few weeks ago, Wikimedia Sverige was invited by the Swedish National UNESCO Commission to a round table conversation on the subject. Other than Wikimedia Sverige, organisations and institutions such as the Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions, the Swedish Research Council, the Ministry for Education and the National Library, took part – many of those who will bear the largest responsibility for putting the recommendations in practice.

These stakeholders shared important thoughts and comments. Perspectives raised included that the recommendation will be an important instrument in the work to change both policy and law. That a national policy is needed. That the required changes will be expensive, and that more resources are needed. That the current merit systems within academia will be difficult and cumbersome to align with open science. And the question of how open science will work in the context of art schools.

Many of the participants agreed that two years of pandemic and two months of the Russian invasion of Ukraine have increased the speed with which world and national leaders work with these issues.

Co-creation, creativity & Citizen Science

Wikimedia Sverige especially highlighted the paragraphs in the recommendation on co-creation, creativity and citizen science. The recommendation points out that academia needs to work with society at large, and we believe that this opens up for a large potential role of the Wikimedia movement. We host one of the largest platforms for sharing information and knowledge, platforms which are co-creative and involve many actors from different parts of society. The movement is also international, and the recommendation wishes to increase international collaboration and co-creation.

We think that this recommendation needs to be recognized in discussions around copyright. The recommendation explicitly references the international intellectual property rights framework, and the importance of flexibilities in this framework:

Further acknowledging that the practice of open science, anchored in the values of collaboration and sharing, builds upon existing intellectual property systems and fosters an open approach that encourages the use of open licensing, adds materials to the public domain and makes use, as appropriate, of flexibilities that exist in the intellectual property systems to amplify access to knowledge by everyone for the benefits of science and society and to promote opportunities for innovation and participation in the cocreation.

These two paragraphs outline the core of what makes the work of the Wikimedia movement possible: flexibilities in the intellectual property system that enable access to knowledge and promote co-creation of knowledge. If these paragraphs would be recognized, the work of the Wikimedia movement – and other actors that strive to amplify access to knowledge – would be much easier, and much more efficient. It would enable exactly the kind of co-creation and citizen science that the recommendation calls for.

The problem, however, is that UNESCO has little influence on the international copyright frameworks – in spite of its central role when it comes to science, culture and education. Instead, it is the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) that coordinate and lead international conversations on copyright.

During the roundtable conversation, I asked the National UNESCO Commission whether they had coordinated at WIPO, at any level. It appears that UNESCO and WIPO rarely and barely coordinate. This is a pity, given the strong support from all member states of these provisions in the UNESCO General Assembly, and the importance it would have for the spread of knowledge if they would become part of international copyright law.

WIPO’s work on copyright has been deadlocked for a number of years. The member states could draw on the UNESCO recommendations to advance this work, particularly in the area of limitations and exceptions to copyright.

The african group has realised the connection between Unesco and the work at WIpo

Two weeks later. I am in Geneva at the forty-second session of SCCR, the WIPO Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights. The African group has prepared a Draft Work Program on Exceptions and Limitations, which is being presented by the delegate of Algeria.

The fifth point of the draft work program says:

“The WIPO Secretariat should convene information sessions and exchanges with Member States, experts, copyright offices and other agencies, and beneficiary organisations, drawing on new or existing research studies where appropriate, on issues relevant the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science (2021) and its implications for international copyright laws and policies.”

Algeria, on behalf of the African group at WIPO, has realised the important connection between the UNESCO Open Science recommendation – approved by consensus late in 2021 – and the work at WIPO.

The question now: will the EU and other countries follow suit?