The EU is working on universal rules on content moderation, the Digital Services Act (DSA). Its co-legislators, the European Parliament (EP) and the Council, have adopted their respective negotiating positions in breakneck time by Brussels standards. Next, they will negotiate a final version with each other.

While the EP’s plenary vote on the DSA is up in January and amendments are still possible, most changes parliamentarians agreed upon will stay. We therefore feel that this is a good moment to look at what both houses are proposing and how it may reflect on community-driven projects like Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata.

Whose rules are we talking about?

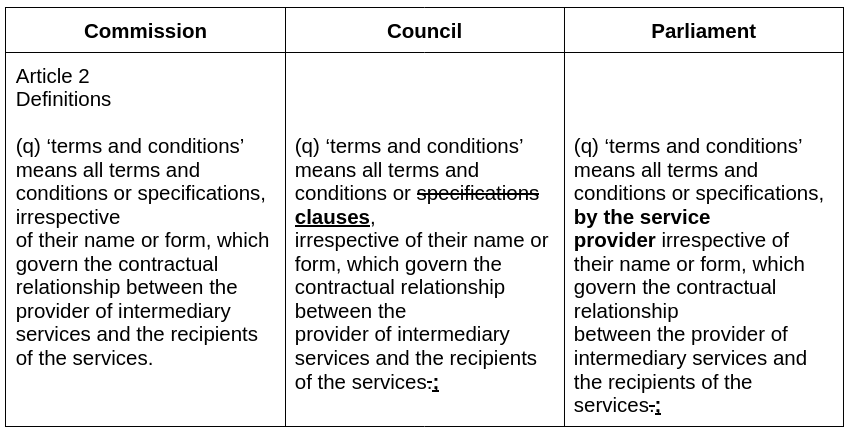

The DSA wants to ensure that content moderation rules on platforms are fair, predictable, understandable and proportionate. It especially targets online platforms’ terms of services. One thing that seemed forgotten in the DSA proposal is that with community-driven projects most of the rules are created and applied by a volunteer community open to everyone. On Wikipedia, for instance, each language community has agreed upon criteria for notability or language style. It wouldn’t be desirable to apply the same obligations to professional lawyers working for the service provider as to volunteers arguing whether Nico Rosberg’s article in Bulgarian should be written with a cyrillic С [s] or З [z]. We wouldn’t want the Wikimedia Foundaiton’s legal team to call the shots on what is considered appropriate transliteration of a German name in Bulgarian.

The European Parliament therefore passed an amendment to the definitions that makes it explicit that the DSA targets the service provider’s rules. This will be helpful.

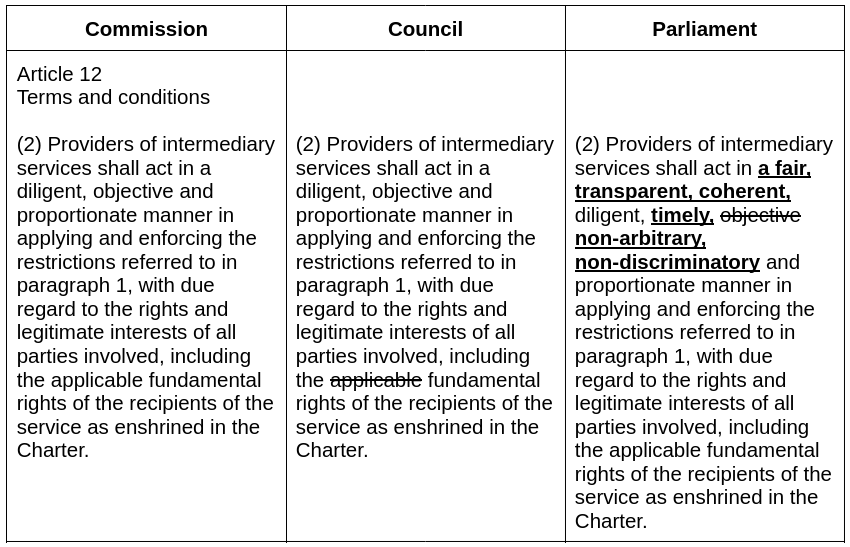

“Objective” vs. “non-arbitrary” enforcement of terms

There is an article that obliges online platforms to enforce their terms of service. It is a reaction to a seemingly common practice for social network providers to write ambiguous rules and to apply them arbitrarily. The text says that providers should act in a “diligent, objective and proportionate manner”. Our worry here might seem benign: We feel that oftentimes objectivity is country and culture specific, while our projects are global. What happens when someone whose posts are moderated, or who thinks someone else’s behavior should be moderated, decides that the moderators aren’t being “objective?” These situations certainly happen often enough, but usually don’t give rise to legal disputes.

We think replacing the term “objective” with the terms “non-arbitrary” and “non-discriminatory,” as the parliament has done, achieves the same policy goal but avoids legal ambiguity.

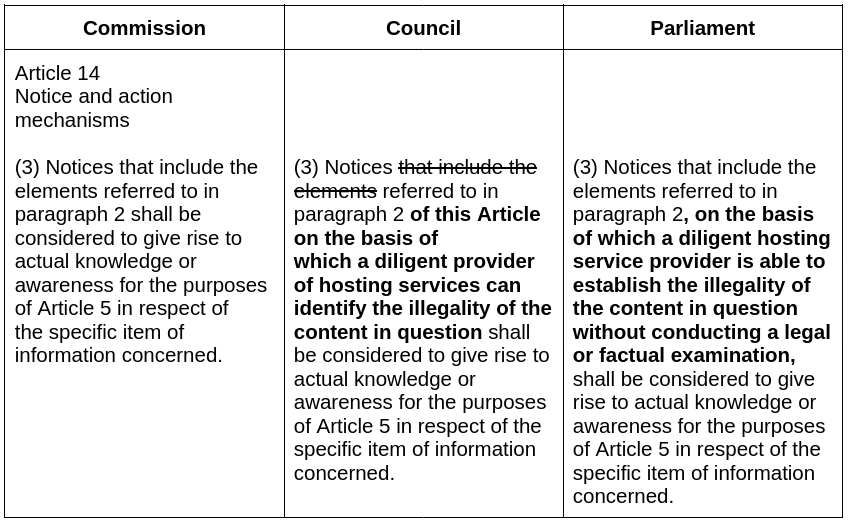

Not every notice leads to “actual knowledge” of illegal content

Online platforms enjoy liability protections for illegal content uploaded by their users as long as they quickly act upon being made aware of it. This principle remains, but the legal question is when there is “actual knowledge” of illegal content. The DSA proposal made it sound like every notice a service provider receives is about illegal content. From a Wikimedia perspective the community does a splendid job in resolving most issues, so that the notices that the service provider, the Wikimedia Foundation, gets are rarely about illegal content. Many notices are by people complaining about their Wikipedia article or photo used, for example. Both the Council and the European Parliament have rearranged Article 14 to make it certain that the service provider has the freedom to assess notices before it is legally required to take action.

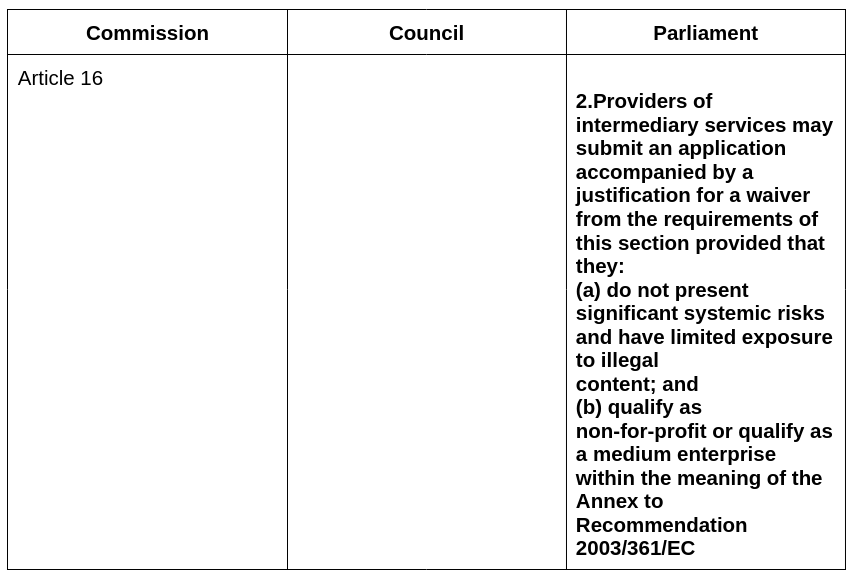

Waivers? Maybe.

The DSA is supposed to create universal content moderation rules. They must apply everywhere on the internet, otherwise users won’t know which rights and options they have.

Some platforms dedicated to archiving knowledge and giving access to the public domain (e.g. the Internet Archive) could not legally operate under the DSA rules. But it is impossible to write an exemption for them without involuntarily watering down the regulation. One attempt to square this circle is to create a waiver system. The European Parliament has introduced one, which means that non-for-profit platforms may apply to the European Commision to be exempted from certain rules under this regulation, as long as they don’t pose a “systemic risk”.

Similar practices exist in trade and competition rules. The downside is that probably only not-for-profits that are professionalised enough will be able to navigate the waiver procedure and that users won’t easily know which obligations apply to which online service. Wikipedia or the Internet Archive could apply to be exempt from rules on “trusted flaggers” and “out-of-court dispute settlements”. This will be very useful for our projects to avoid disruptions to functioning community content moderation models, but it won’t solve the main issues for online archives.

Which regulator will oversee Wikipedia?

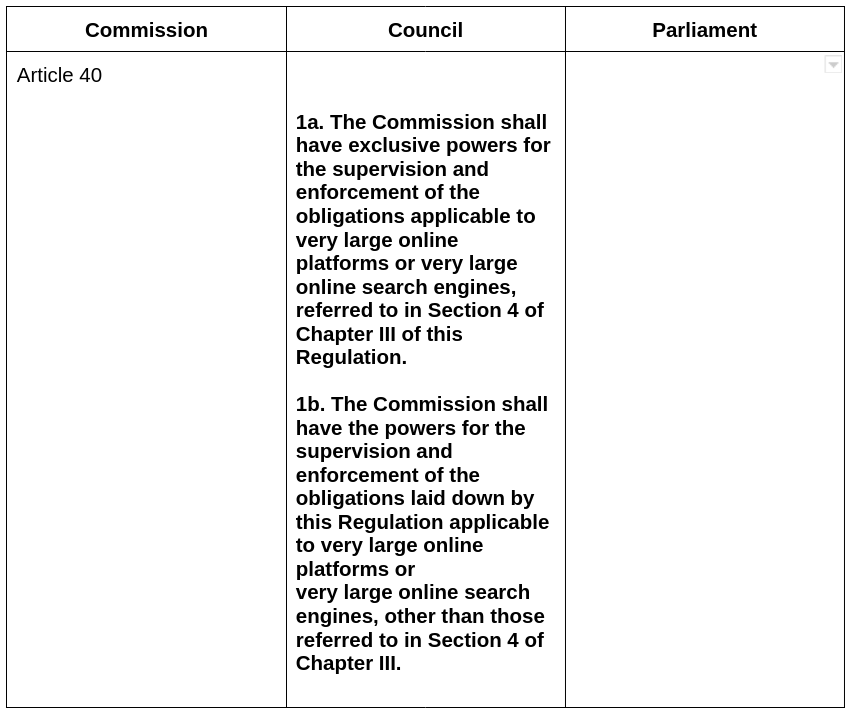

One of the fundamental questions about each and every EU legislation is who will have the competence to supervise and enforce it. Originally the Commission proposed to put national authorities (Digital Services Coordinators designated by each Member State) in charge. The Council changed this by saying that very large online platforms, a category which Wikipedia will most likely be part of, will be in the competence of the European Commission, while other platforms will remain national competence.

As global projects, for us it makes sense to talk to regulators whose jurisdiction spans across borders, which is why we welcome this. On the other hand we might end up in a position where our smaller projects are regulated by national authorities, while the connected Wikipedia is regulated by the European Commission. Furthermore, the multiple roles the Commission plays – as an executive body, a regulatory agency and a body that initiates legislation – creates tension.

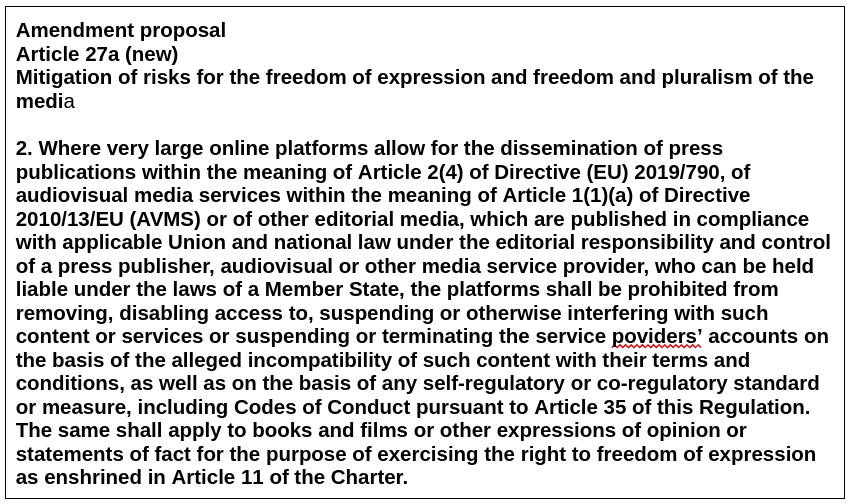

Media exemption

One amendment proposal that did not pass the committee vote in parliament, but will be put to vote again in plenary is the so-called “media exemption”. It would prevent very large online platforms (VLOP) from down-ranking, deleting or labelling content coming from press publications (think TV stations and newspapers). The political aim of this is to give traditional media additional clout in the online space. But are all registered media outlets reliable sources of information? Does their content belong anywhere they decide to upload it? The amendment seems not well thought out and worries us, which is why we urge the EP to reject this in its plenary vote as well.

Next up: Plenary vote & trilogues

The plenary vote in the EP will take place in the second half of January. After that the inter-institutional negotiations (a.k.a. trilogues) will begin.

Based on the examples above we can see that the DSA was written with mainly the for-profit, dominant platforms in mind. The Commission proposal does a good job at categorising different types of online services, but it also seems to omit the presence of alternative platform models and content moderation practices. The European Parliament and the Council have taken several steps to remedy this by introducing fixes that should be kept.

If the co-legislators want to really step up the game in reshaping the online platform space, they should not only focus on curtailing very large platforms’ power, but also commit to supporting alternatives to the dominant operation model. Public-interest platforms driven by vibrant communities are such an alternative.